Once in a while I enjoy being a total spreadsheet nerd. Perhaps more often than I like to admit.

Recently a client has asked me to do some very large Roth conversions for his IRA. He showed me this website which ran various scenarios on all his accounts. To my surprise, the more he converts his traditional IRA early on, the higher his projected ending balance gets at the end of his projected investment horizon. The “improvements” shown were not small, either. We are talking millions of dollars. This is contradictory to our experience.

So I rolled up my sleeves and ran some scenarios on the spreadsheet, and proved common sense prevailing. As it turns out, for most people, it does not make sense to do large Roth conversions and pay a lot of money to the IRS up-front. It simply does not make sense to bump ourselves up into higher tax brackets, pay more taxes, and yet expect better results. Also, no one really knows what the future tax rates will be.

Let’s look at the numbers through the lenses of Mr. and Mrs. Doe.

Suppose Mr. John Doe and Mrs. Jane Doe are happily married. Mr. Doe is 67 and Mrs. Doe is 66. They have saved up some money and enjoy a peaceful retirement. They have saved up close to three million dollars ($3,000,000). The kids have long left the nest with big jobs. Life is good.

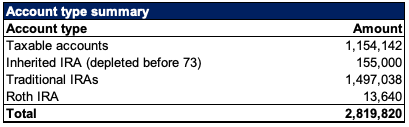

Here is an overview on how much they have saved.

Mr. Doe, like myself, is the geeky kind. He found on the web that the more you convert to your Roth IRA, the more money you make. But it bumps him up into high tax brackets in the years he makes those conversions. So he ran some good-old “sensitivity analyses” to double check what he sees on the internet. We can’t just trust anything we see on the web nowadays.

Mr. Doe is the cautious kind. He wants to project inflation rate high and his investment returns low. After all, he wants to make sure he has enough for both himself and his wife to live to 100. Here is the economic assumptions:

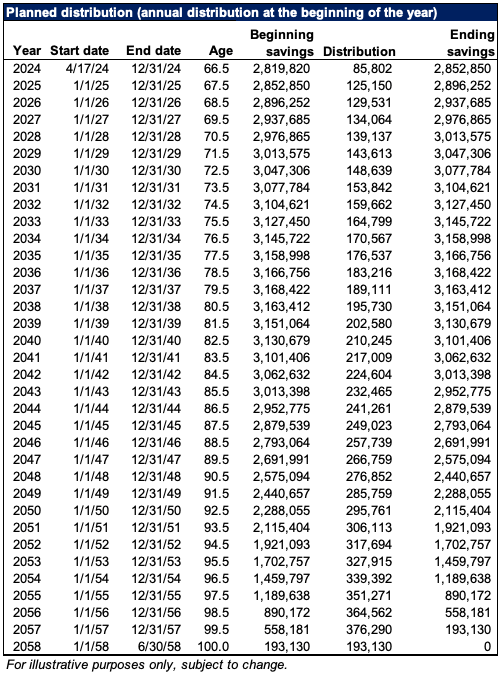

He finds out that, with the money he saved up, he can spend around $120K in 2024 dollars, and increase that annual spend by the inflation rate 3.5% each year to keep up with his lifestyle. If the market is up, he may feel safe to take a little more. If the market takes a dive, he might tighten up a little.

Now, for the real nerdy part. He ran 3 scenarios to test what he saw online. Each scenario assumes that tax laws don’t change – meaning we keep tax law change as a “constant” factor, and analyze the variables.

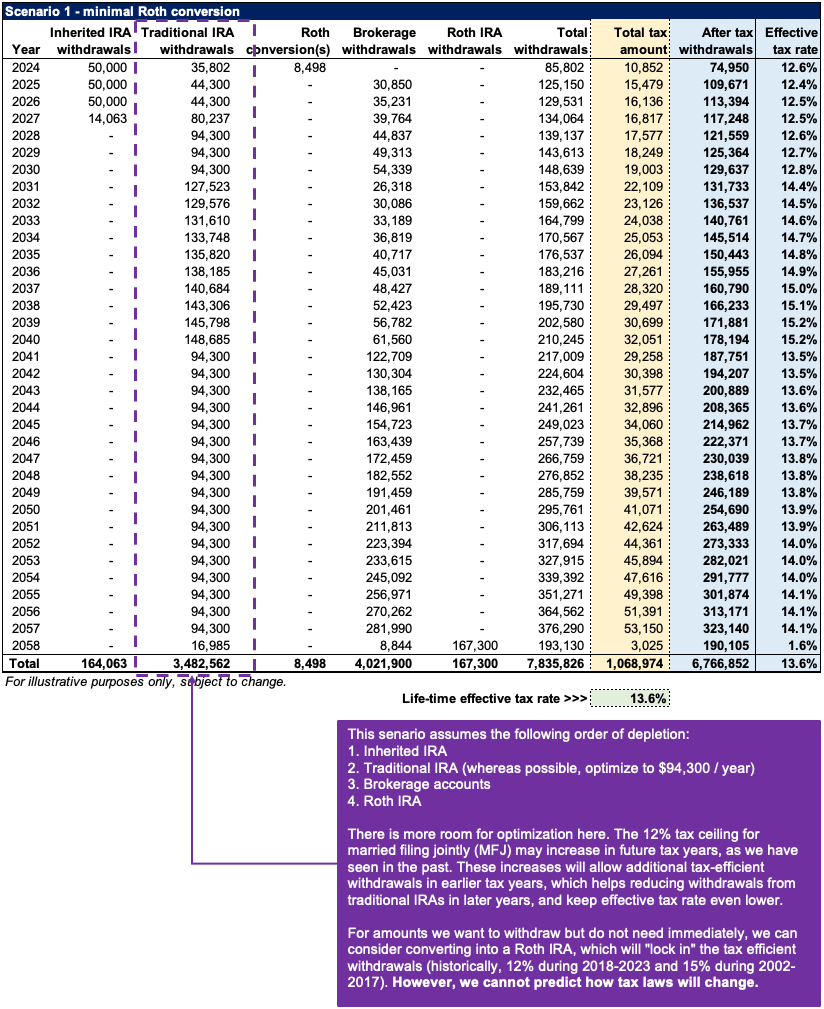

Scenario 1 – minimum to no conversion

The first scenario, Mr. Doe would just keep things as-is. Doesn’t really do much Roth conversion. He would first deplete the inherited IRA, as they come with a mandated depletion window nowadays. Then the household traditional IRAs. Then the brokerage accounts. And finally, the Roth IRA. He figures he would spend down the “regular income tax” accounts first, because if his children get to inherit the accounts, they would have to pay much higher taxes because they all have pretty good jobs and still in their high income earning years.

The same depletion order is used for all three scenarios.

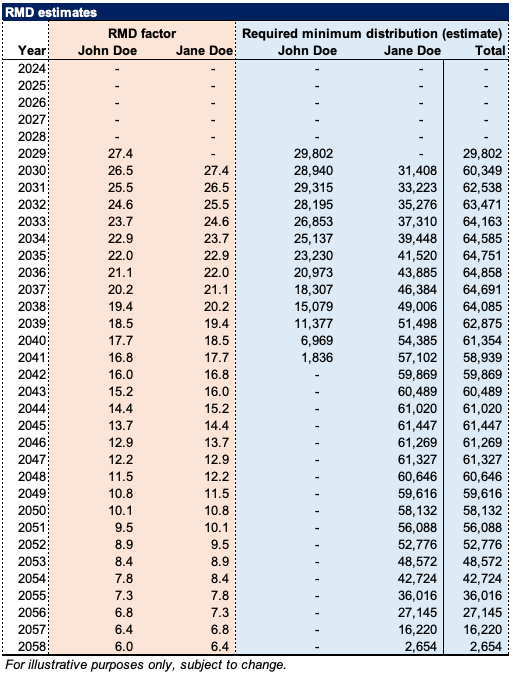

After the inherited IRA, the household IRAs are consumed through the years. Where possible, total annual distributions from traditional IRAs are kept at $94,300. Assuming 2024 tax laws, this is the ceiling for the 12% tax bracket for a married filing jointly household. This is even lower than the 15% long-term capital gains tax rate. Some of the money needed to come out in early years to fully deplete the accounts. Overall, the Does would have a lifetime effective tax rate of 13.6%, with each year’s tax bill increasing on a pretty steady pattern. The Required Minimum Distributions (RMD) each year is also satisfied. Not bad.

Over the years, the Does may consider converting small amounts into a Roth IRA account, for money they can withdraw at low tax rates, but do not immediately need. This will help them “lock-in” the tax-efficient withdrawals.

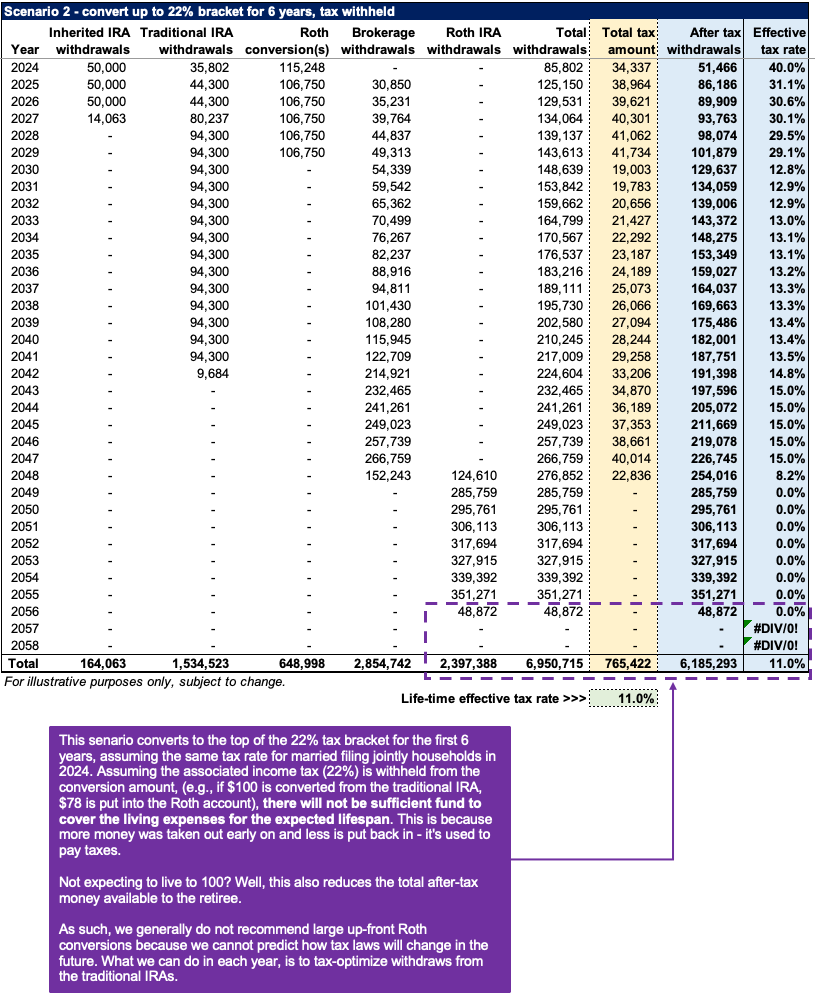

Scenario 2 – convert to the top of the 22% bracket for the first 6 years, withhold taxes.

Mr. Doe then runs a second scenario, similar to what he saw on the inter-web. In this scenario, the Does make Roth conversions to the top of the 22% tax bracket for the first 6 years. They do not want to suffer the cash outlay to pay estimated taxes up front when the conversions are made, so the taxes are withheld (e.g., if $100 is converted from the traditional IRA, $78 is put into the Roth account).

In this scenario, Mr. Doe finds out that he will simply not have enough money to support himself and Mrs. Doe through their projected lifespan. The reason is simple: more money was taken out of the accounts early on, and less was put back in. The difference went to the IRS. This also means fewer dollars would be available to the Does during the last few years in life, with no room to tax-optimize. Mr. Doe paid taxes on every dollar in the Roth account earlier at 22%. Whether or not that will turn out to be a good thing, no one knows now.

On the flip side, you would see that every dollar Mr. Doe took out later in life was after tax, so more went into his bank account in those years. He could lower the withdrawals in those years, and that would bring this scenario back to somewhat a break-even with Scenario 1 – because that’d be exactly how it works out mathematically. I failed to observe the millions of dollars in improved ending balance promised by the website Mr. Doe showed me.

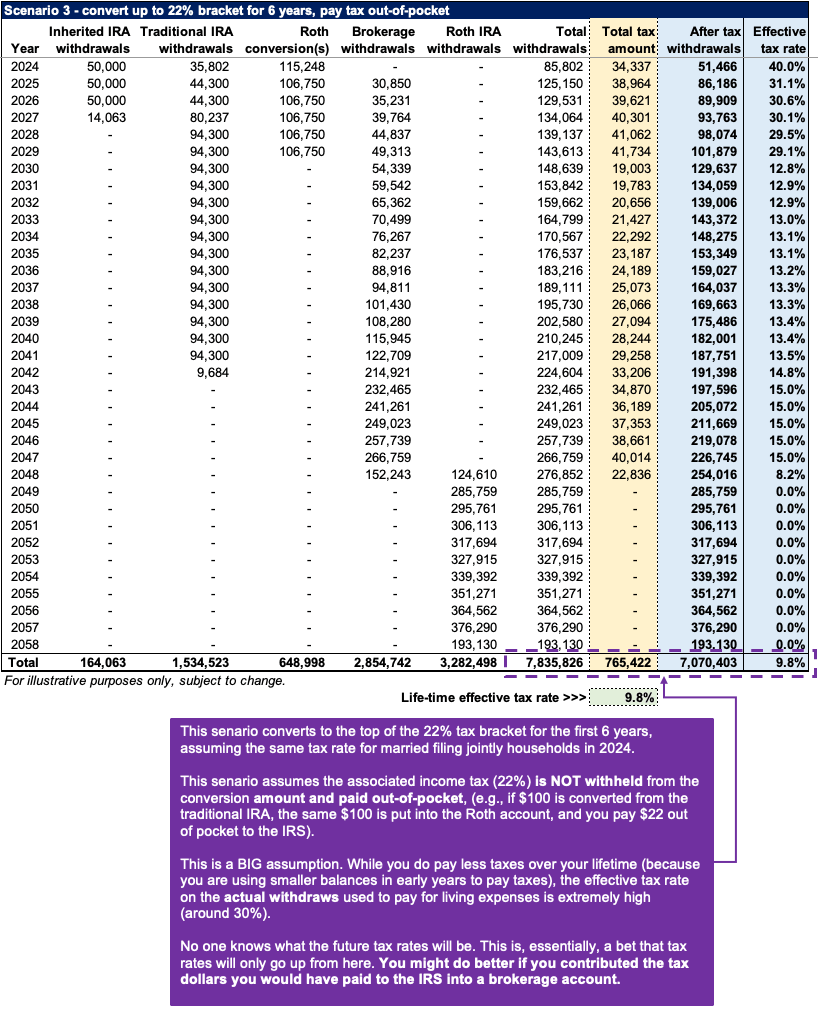

Scenario 3 – convert to the top of the 22% bracket for the first 6 years, pay taxes out-of-pocket.

What if Mr. Doe put 100% what he converted into the Roth IRA? In this scenario, all the converted amounts are put into a Roth IRA, and the tax associated with the conversion are paid out-of-pocket.

On first glance, this scenario looks like the best way to go. Many would have stopped at the 9.8% life-time effective tax rate. But Mr. Doe is not one of the many. Mr. Doe is careful. He realizes that:

(1) this scenario only works because he paid large sums of money to the IRS out-of-pocket to the IRS during the first 6 years. About $140K to be exact (not shown above, columns were hidden to fit the table). This tax payment in and of itself is akin to additional contribution. He may have the money, he may not. He may want to just keep it in a brokerage account. These checks to the IRS are not always pleasant to write.

(2) Assuming tax laws do not change past 2024 is a BIG assumption. No one knows what the future tax rates will be, and this is, essentially, a bet that tax rates will only go up from here. In placing this bet, the Does would have to suffer extremely high effective tax rates on ACTUAL withdrawals in early years (around 30%). This simply does not make sense.

I hope the scenarios bring some clarity and focus if you are considering a Roth conversion. Like I said in the very beginning, it does not make a lot of sense for most people to do large conversions up-front early in their retirement. One cannot expect to pay more taxes up-front in higher tax brackets, and get better results, at least not from an investment management perspective. How that website estimated better investment results by doing large up-front conversion, frankly, is beyond me. I understand it is not my place to judge other people’s intentions, nor do I have complete knowledge to replicate their algorithm. However, it did look like they were selling services.

If you read this far, I sincerely thank you. Please let me know if I have left anything un-mentioned. Also, if you would like me to walk you through the whole model, please send me an email from the Contact page. I’ll be happy to walk you through.

Disclaimer – the content of this blog is simply our opinion, and does not constitute as tax, financial, or legal advice. I do not claim to be a tax expert and there can be things that I missed. We simply want to be helpful and put out good educational information for people. Please don’t sue us.

Leave a comment